Social psychology in modern horror: a review of sociological concepts in The Witch & The Lighthouse

- Post by: Psyche General

- 24.07.2024.

- Comments off

Bianka Crnković

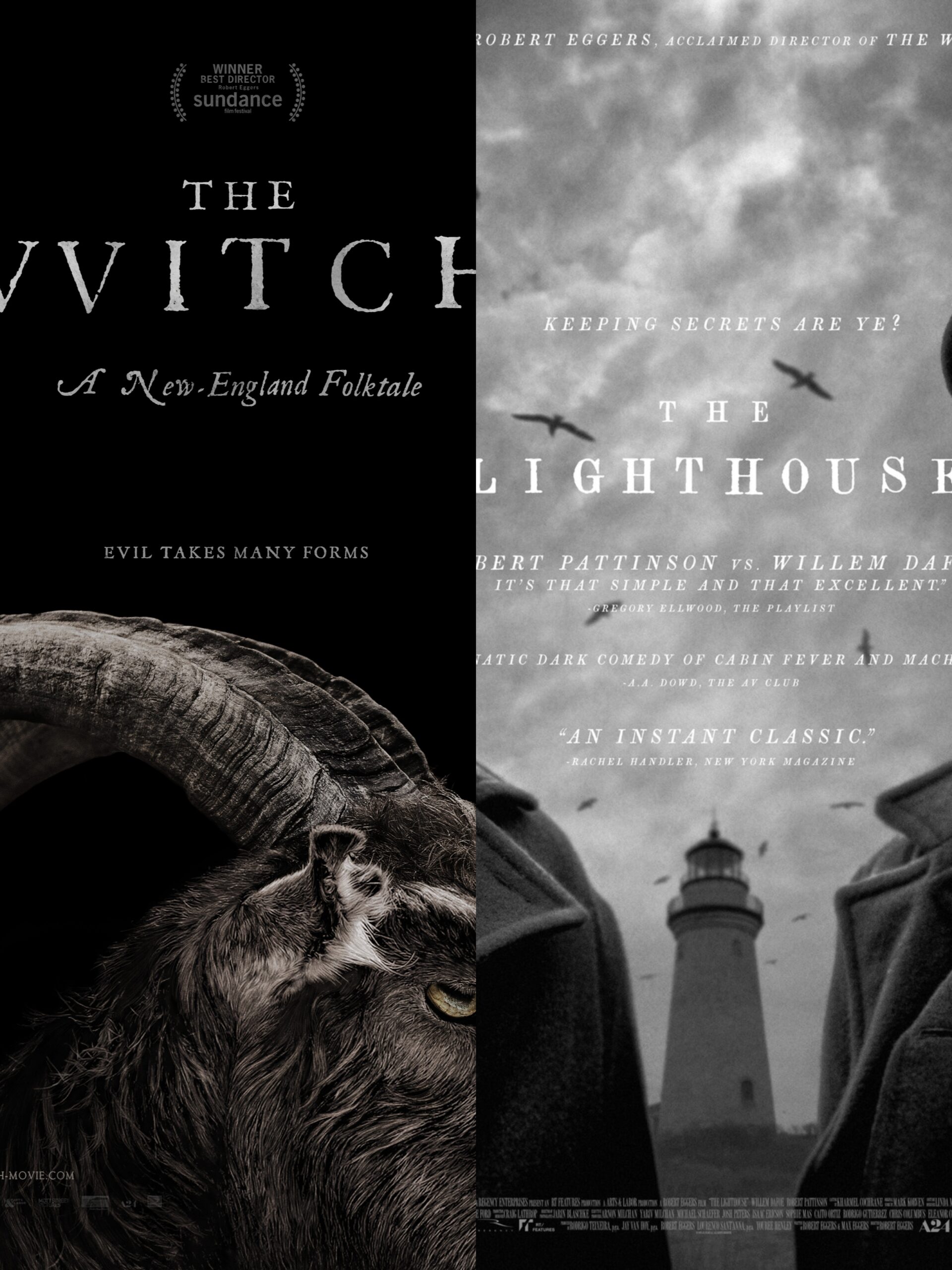

Social psychology had long been a matter of interest for the wider public, which hardly comes as a surprise. The definition states that social psychology explores how the real or imaginary presence of others influences our thoughts, feelings or actions (Allport, 1985). Naturally, a lot of concepts characteristic for social psychology found their way to the big screens – one of the most famous examples being “12 Angry Men” and “Rashomon”. Both of the movies are considered masterpieces, making them subject of many reviews and studies published throughout the 20th century. However, the interest for social psychology has not diminished in the 21st century. In this article, we will examine two recently released features directed by Robert Eggers which tackle sociological concepts in a contemporary way.

Eggers is an American film director, screenwriter, and production designer. In 2015, he caught the public’s eye with his debut feature The Witch, which went on to win multiple awards, including the Sundance Directing Award. The film had an amazing reception, grossing a worldwide total of $40.4 million, with some calling it a masterpiece of modern horror. Writing for Variety, Chang (2015) calls the film a “strikingly achieved tale of a mid-17th-century New England family’s steady descent into religious hysteria and madness”.

Fuelled by the film’s unexpected success, Eggers – now with an elevated directing profile – releases another instant classic – The Lighthouse. Originally imagined as an adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s unfinished short story with the same title, the film had undergone massive changes in the script and concept before being released in theatres. The audiences were captivated by the story of two lighthouse keepers struggling to preserve their sanity while being completely isolated from the rest of the world. Once again, Eggers’ indisputable talent came to light, solidifying his reputation as a director who creates true horror by exposing it in the relations of his characters. To understand the complexity of the relations in question, a thorough analysis of both of his features is required.

The Witch, subtitled A New England Folktale, is a period piece set in the 1630s. The feature follows a Christian family which is forced to relocate to the edge of a secluded forest after being banished from a Puritan plantation. William, the father and patriarch, together with his wife Catherine and children Thomasin, Caleb, twins Mercy and Jonas, and new-born Samuel, looks at the exile as a blessing in disguise – a chance from God to start anew. However, after Samuel mysteriously vanishes while being watched by Thomasin, the family falls in a state of grief and guilt. As the firstborn child, and the only one present at the time of Samuel’s disappearance, Thomasin becomes the family scapegoat – her pious, yet bitter mother, blames her for every inconvenience that falls upon the farm. The lack of support from her father, as well as the twins’ conviction that she is indeed a witch, help to create an atmosphere of uneasiness and distrust, which culminates in the frightening possession and eventually death of the second eldest child, Caleb. We learn that an evil force is indeed lurking in the woods and causing misfortune of the family. However, as William and Katherine start to succumb to madness and paranoia, it becomes evident that they are also to blame for their ultimate downfall. The film ends with Thomasin as the sole survivor of their family, who joins the witches in the forest as they accept her as one of their own.

The first aspect which may be of interest to a social psychologist is the expulsion of the protagonists from the Puritan settlement. In their state of exile, the family builds a farm on the edge of a secluded forest, which create an unnerving feeling of claustrophobia and isolation. However, what induces the fear in the viewer is not the dark forest which looms over them, but the feeling of loneliness and helplessness, knowing that they have to face whatever lurks in that forest alone. Expulsion, or rather separation from the group, has long been used as a form of punishment: from ostracizing deviant members in ancient times, to solitary confinement in modern prisons. Besides psychological damage, ostracism causes physiological deregulations – it impairs immunological functioning and interferes with hypothalamic reactions related to aggression and depression (Williams, 1997).

The family’s only active connection with their previous settlement is their faith, to which they turn blindly. They become obsessed with the concept of sin, especially God-fearing Caleb – living under the brooding assumption that their every move was scrutinized by a higher power. This movie can be seen as an example of religious fundamentalism leading to paranoia and hysteria: as mistrust and contempt for her daughter grow, Katherine, blinded by rage and grief over Caleb’s death, eventually locks Thomasin up in the pen, convinced that her own child is the source of evil which follows them.

The events that unfold in this feature were inspired by the uncertain times prior to Salem Witch trials. Chang (2015) points out for Variety: “We’re watching not just a private tragedy but a prequel to a larger-scale catastrophe, sowing seeds of suspicion, violence and fanatical thinking that will be passed down for generations to come”. Quite so, as what followed was a series of prosecutions, trials and executions of people accused of witchcraft. In the events of Salem Witch trials, as in the witch hunts which occurred in the same period in Europe, we can see an example of group polarisation, a tendency for group members to adopt more extreme attitudes or actions than the initial attitudes or actions of individual group members (Aronson et al., 2005).

Another aspect worth analysing is Thomasin’s transformation from a devoted daughter to the “Devil’s handmaiden”. Here we are faced with a chilling example of self-fulfilling prophecy, defined as a process in which a person’s expectations about someone can lead to that someone behaving in ways which confirm the expectations (Aronson et al., 2005). In the case of The Witch, we see Thomasin in an unenviable position when, after a joke that was taken too seriously, and a series of unfortunate events that all coincidentally point to her as the culprit, her family begins treating her as the source of all evil. In the end, nothing is left for Thomasin except to become the very creature she was accused of being.

Similar to The Witch, The Lighthouse is also a period feature, this time set in the early 19th century. The film centres around two characters tasked with manning the lighthouse on a desolate island, far away from civilisation – isolation being another thing that the two movies have in common. Two men, Thomas Wake and Ephraim Winslow, whose real name we later find to be Thomas Howard, arrive on the island with a boat that is not set to come back for another six weeks. Howard passes his day doing manual labour and other undesirable tasks delegated by Wake, a senior lighthouse keeper who covets the light for himself – Howard is not allowed to man the light, even though they should be alternating in keeping in lit. Soon their relationship turns sour, as Wake proves himself to be an unpleasant, superstitious and bitter man, humiliating Howard whenever he gets the chance. We also learn that Wake worships the light of the lighthouse on a fanatical, almost perverse level, removing his clothes and facing the light with a dazed look in his eyes. The lighthouse keepers, or wickies, manage to hold out those six long weeks, but on the day the relief was supposed to come, a terrible storm traps them on the island. As a response to living in desolation and despair, Howard turns to liquor and gives in to hallucinations that have been haunting him since the arrival on the island. At one point, we cannot differentiate reality from Howard’s alcohol induced fever dreams. As their rations become scarce, Wake and Howard spiral into madness, spending their time almost delirious. The story reaches its peak when Howard finds Wake’s logbook and realises he’s been planning to send him off without payment. Enraged, he attacks Wake and kills him. Howard then rushes to the light and finally gazes upon it, which proves to be fatal – he trips and plummets down the stairs to his death.

One of the most interesting aspects worth observing is the behaviour of our characters: being a lighthouse keeper is a deeply lonely and isolating job, especially when the only company is someone you grew to despise. Like many other trapped on the sea, Wake and Howard eventually turn to alcohol, which only brings out their repressed thoughts and emotions. Alcohol impairs the cognitive mechanisms responsible for inhibition of certain behaviours, such as aggressive behaviour, self-disclosure and sexual advancement (Steele and Southwick, 1985). All three of these behaviours can be noticed in multiple scenes: Wake and Howard drinking at the dinner table, which progresses into a scene of mad dancing, furniture-breaking, fighting, embracing, slow-dancing, crying and sharing their darkest secrets.

Another interesting aspect of their relationship is gaslighting. Defined as a type of psychological abuse which makes its victims question their sanity, gaslighting can often be found in power-laden intimate relationships (Sweet, 2019). Wake, who is Howard’s superior, gaslights Howard at multiple occasions, making him question the amount of time they have been trapped on the island and even his own actions: at one point, Wake destroys the lifeboat, chases Howard with an axe, and then convinces him that it was the other way around. Seeing how the two men are alone on the island, with no other way to fact-check reality, it comes as no surprise that Howard begins to lose his grasp on sanity.

Howard is also tormented by hallucinations, caused by guilt, isolation, liquor, or a mixture of all three. When his delirium reaches its peak, even the viewer isn’t sure what is real, and what is the product of his tormented imagination. However, there may be another cause of his and Wake’s madness – mercury poisoning. Since the Fresnel lens, which was used at the time in lighthouses, was extremely heavy and had to revolve constantly, the lanterns floated on a bath of mercury which is now known for its toxic properties. Exposure to mercury and its odourless vapour can cause a wide array of neurotic side effects – memory loss, mood swings, anxiety, delirium, and confusion (Walter, 2002).

In this review, we examined sociological concepts like ostracism, self-fulfilling prophecy and gaslighting, and their representation in modern cinematography. Although the main focus of this article was the filmography of Robert Eggers, there are many more prolific directors whose movies merit an analysis. The concepts of social psychology remain ever-present on the big screens, and with the rapid changes in society as a whole these past few years have brought, one can only imagine how they will be represented in the years to come.

Literatura

Allport, G. W. (1985). The historical background of social psychology. The handbook of social psychology, 3(1), 1-46.

Aronson, E., Akert, R. M., & Wilson, T. D. (2005). Socijalna psihologija. Mate d.o.o.

Chang, J. (2015, January 23). Film Review: ‘The Witch’. Variety. https://variety.com/2015/film/reviews/sundance-film-review-the-witch-1201411310/

Fear, D. (2019, October 25). Drunken Sailors and Movie Stars: Robert Eggers on Making ‘The Lighthouse’. Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-features/robert-eggers-the-lighthouse-interview-898545/

Kermode, M. (2016, March 13). The Witch review – original sin and folkloric terror. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/mar/13/the-witch-film-review-robert-eggers

Steele, C. M., & Southwick, L. (1985). Alcohol and social behavior: I. The psychology of drunken excess. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.18

Sweet, P. L. (2019). The sociology of gaslighting. American Sociological Review, 84(5), 851-875. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419874843

Walter, M. (2002). Lighthouse Keeper’s Madness: Folk Legend Or Something More Toxic?. History of Medicine Days, 190.

Williams, K. D. (1997). Social Ostracism. Aversive Interpersonal Behaviors, 133–170. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-9354-3_7